Suunto Blog

The data rules! A pro triathlete’s data driven training approach

When Cody Beals became a triathlete cycling was his weakest discipline. At high school, he was a District All Star in cross country, and a good swimmer. But cycling wasn’t his thing.

The reverse is now true – cycling is his strongest discipline. And it was a data driven approach to his training that made the difference.

For proof, the 28-year-old from Guelph, Ontario won two full distance Ironmans, the first and second of his career. At his first, Ironman Mont Tremblant, he set the bike course and overall course records.

“I undertook a deliberate process of figuring out how to get my cycling up to a world class level,” Beals says. “The biggest thing was getting a power meter – it was a huge revelation! I was wasting so much time on the bike just soft pedalling. With a power meter I learned to make every minute of my riding count.”

© Welle Media

Beals has always been a data freak. He was top of his class at high school, and top of a prestigious physics programme while at university. Back then, he began capturing and analyzing data almost obsessively.

“I made my own monster spreadsheet to track every single last aspect of my life,” he says. “My sleep, my mood, my training – everything. That was when I was a self coached athlete. Even though I was making mistakes, a data approach was always something I believed in.”

After university, Beals has worked in statistics and data analysis, and is using his mastery of these skills to optimise his training. His coach, David Tilbury-Davis, shares a data based training philosophy, and the two work together on that basis. All Beals’s swim, bike and run training is measured and monitored. “The data tells the most compelling story,” he says.

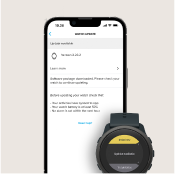

Data analysis has also helped Beals in other ways. Having a Suunto 9 to capture his training runs shows Beals what’s really going on with this runs, not just what he thinks – two very different things. Perceived exertion doesn’t necessarily equate to good performance.

“I've learned through data that how you feel about something sometimes bares no relation to how you're actually performing,” Beals explains. “How I'm feeling is another data point, but it's not the most important. In the absence of power, pace or heart rate data you're just left guessing. The coach can provide part of the reality check, the rest of the reality check comes from these devices and the data they collect.”

© Welle Media

While how he feels about a workout isn’t the most important factor, conversely it is a potentially telling data point. Feeling over the moon isn’t necessarily a good sign, while feeling average isn’t always a bad one.

“I like that the Suunto 9 will prompt you for how you're feeling after each workout, he says. “That's something I have started monitoring more closely. What I've learned is that in a lot of my best training blocks, with almost every single workout, I will feel very medium.

“People assume if you're crushing it leading up to an Ironman, you're feeling great about every session, or maybe some people would assume you are so tired and fatigued that every session is brutally hard.

“The reality is that when I'm putting in my best training blocks, I'm just very stable. Everyday is pretty unremarkable. I'm not putting up epic training sessions. My mood isn't swinging around wildly. It's just day in day out consistency.”

This and other insights help Beals and his coach from avoiding overtraining syndrome, which Beals says is too often a badge of honour in the world of triathlon.

“It's kind of celebrated when athletes can push themselves to extreme lengths in training, but I will tell you that any moron can overtrain themselves,” Beals says. “The hard part is the deliberate, methodical application of training load and on the flip side recovery to reach your true potential.”

Lead image: © Ventum

READ MORE:

SLAYING HIS DEMONS: A PRO TRIATHLETE’S JOURNEY TO FINDING BALANCE

William Trubridge swims like a dolphin across wild New Zealand channel

New Zealander William Trubridge has emerged from the Cook Strait jubilant after becoming the first person to complete a channel crossing by swimming underwater.

Trubridge used his incredible breath hold diving ability to swim under the surface, like a dolphin, before surfacing, and diving under again, all the way across. He followed conventional channel crossing rules, such as not resting on a boat or float, except for two changes: all propulsion had to take place underwater on a breath hold, and the use of a wetsuit and fins/monofin was permitted.

“We had strong currents and cold water patches, rough seas, it was like being in a washing machine at times,” he says. “I was getting cramps, cold, blisters, the usual stuff. But I still feel like I got off lightly; there were so many things that could have been different, and for each one of those I probably wouldn’t have made it. I’m feeling a lot of relief and jubilation at the end to make it.”

The Cook Strait separates New Zealand’s North and South islands, and is considered one of the world’s most unpredictable and treacherous stretches of water. At it narrowest points, it’s a mere 22 km across. But what it lacks in lengths it makes up for in fierceness: wild unpredictable weather and powerful currents, chilly water that can cause hypothermia, stinging jellyfish and a population of curious sharks.

“Crossing the Cook Strait is like trying to hit a bullseye, with the target on the back of a bucking bull,” Trubridge says. “The currents are so powerful, and reversed direction at least three times during the swim, mean that hitting the closest piece of land (Perano Head) required constant calculations and course corrections. I’d heard many tales of channel swimmers coming within 500 m of land and battling against currents for another four hours before succumbing to cold and fatigue without reaching the shore.”

The decision to attempt the first “human aquatic crossing” was made suddenly when a good weather window coincided with advantageous low tides. Trubridge had previously done only a few six to eight-kilometer training swims to prepare. “I knew I wasn’t really built for this kind of thing,” he says. “My sport (depth diving) is primarily anaerobic fitness, so I don’t have well developed aerobic muscle fibers. My body type is pretty much the exact opposite of what you need to have for this kind of cold water swimming.”

Thoughts about the plight of New Zealand’s Hector’s and Maui’s dolphins, and wanting to save these precious and intelligent animals, kept Trubridge moving forward despite the challenging conditions and 15-18 degree water. “The main reason for doing it has always been to bring more awareness to the situation with the dolphins,” Trubridge says. “These are the two subspecies of New Zealand dolphin that occupy the North (Maui's Dolphins) and South (Hector's Dolphins) islands. Both subspecies are threatened by extinction.”

Trubridge is calling on the New Zealand Government to act quickly to save the dolphins. The fishing industry must be better regulated to protect the dolphins. He invites divers around the world to put pressure on the New Zealand Government to act before it’s too late.

“I made it across about five times slower and with five times as many dives as it would take a Hector’s Dolphin to make the same crossing, but it showed that if we can swim like a dolphin between our two islands then they too should have the freedom to do the same.”

WATCH NOW: Will Trubridge crosses Cook Strait "like a dolphin"

How to swim like a dolphin

Watching Suunto ambassador and freediver William Trubridge swim underwater like a dolphin across New Zealand’s wild Cook Strait, it’s easy to believe he possesses some sort of preternatural ability. There are, after all, few people on the planet who can swim 32 km in that manner for nine hours and 15 minutes.

In March this year, Trubridge achieved a world first: he swam under the surface of the strait before surfacing, and diving under again, all the way across, using the dolphin kick to propel him. A channel crossing of this kind had never been done before.

He did it to raise awareness about the plight of New Zealand's endangered Maui and Hector's dolphins. During his swim, his Suunto D6i Novo dive computer recorded 943 dives. Watch the short clip below below to see him in action.

Mastering the dolphin kick didn’t come easily to Trubridge. He’s had to work at it. “When I first started free diving, I struggled with the movement, and it’s probably because I never swam butterfly at high school,” he says. “It’s not a natural movement for me. It requires a lot of flexibility in your whole back and I didn’t have that at first. I still don’t have it to the same degree as some other free divers.”

He has patiently practiced the technique over a number of years. All that training has paid off. Who better to ask about how to develop a powerful dolphin kick?

Trubridge did his epic swim to bring attention to New Zealand's dolphins and to pressure its Government to protect them.

Why master the dolphin kick?

Simple answer: it feels awesome. “You can really fly through the water at a good speed for a human being,” Trubridge says. “It’s fun to play in waves. You can swim towards a wave as it’s about to break and jump out the back of it like dolphins do. Or you can swim down to 10 m, turn around and swim back up as fast as you can and actually breach clear out of the water because of your speed. It’s a lot of fun to play around with a monofin.”

It’s also an important stroke for freediving, especially for the Constant Weight discipline. Using a monofin and a dolphin kick is the most efficient propulsion, and is best the way to dive the deepest and longest.

How is it done?

It’s the same stroke as butterfly swimming, however it’s done underwater. A monofin or flippers are used in freediving to gain a bigger surface area for propulsion. “The movement is generated by an oscillation of the pelvis, forwards and backwards, controlled by your lower back, and abdominal muscles,” Trubridge says. “It starts a wave that’s sent down your legs into the fin. In order to transmit that wave efficiently you need to keep your legs straight, using your quadriceps, hamstrings and calves. Your upper body, ideally, stays pretty stationary. You can have your arms out in front of you which is a lot more streamlined, or by your sides which is more relaxed.”

How to develop the underwater dolphin kick?

Technique before power

One common mistake, Trubridge says, is to start out practicing the dolphin kick with a monofin. Because the monofin is so powerful it compensates for bad technique. “You can bend your knees, and move inefficiently, and still get good propulsion with a monofin,” Trubridge says. “My advice is to always start with something that doesn’t have the same surface area, like really small flippers, and practice dolphin kick with those, which will be a lot more difficult.” Alternatively, try without flippers.

The practice: Underwater, extend your arms and try to dolphin kick and get good speed. Don’t be put off if you don’t move forward at all; it takes time to develop the technique.

Vertical dolphin

Position yourself vertically in deep water with just your head and shoulders out of the water. Extend your arms above your head. Now, try the dolphin kick, keeping yourself as high above water as possible while staying in the same spot. “It becomes tiring very quickly,” Trubridge says. “It trains the muscles you need in your core and legs, and after a while you will find yourself slipping down into the water.”

Land-based exercises

Any exercise that improves core and leg strength will help. However, Trubridge says specificity of training is important. “Squats, crunches, those sorts of things, will target those muscles, but I prefer to target them in a way that is more specific to the way they are being used in the stroke,” he says.

Hanging bar exercises

Swinging: Find a hanging bar, and hang from your hands, with your palms pointed away from you. Using your core muscles, swing your legs back and forward, keeping them as straight as possible. Don’t use momentum to swing, but rather the abdominal muscles.

Pike pull up: From the hanging bar, do a pull up with your legs in the pike position, or in front of you at a right angle to your upper body.

Monofin or flippers?

The monofin is the best for deep dives, maximum speed and efficient movement. The downside is they are hard to wear for long periods of time. They have to be strapped to the feet very tightly, which can cause blisters and cramps.

Flippers are better for relaxation, recreation – spearfishing and snorkelling, for example – and for training. They offer more versatility.

The art of battle: 6 tactics to slay your competitors

Let your plans be dark and impenetrable as night, and when you move, fall like a thunderbolt.― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Pro triathlete Cody Beals loves a good race battle. He’s been having them since his high school cross-country days. More recently, he fought it out against two athletes at the inaugural Challenge Cancun triathlon, ultimately placing second. Cody thrives on competition, and is not afraid to employ deception to defeat his rivals.

The most dramatic battles, he says, are when you are neck and neck with another athlete. Knowing how to do battle is an important part of triathlon. It’s something that can be trained, and requires a certain degree of cunning. Cody shares his tactics.

6 tactics to overcome your rivals

1. Let them do the work

The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Cody advises to sit back and let your rival work for you. He learned this the hard way after many years of trying to be at the front of the pack, especially on the runs. He expended so much energy doing this he got his butt kicked in finishing sprints over and over again. He eventually learned it’s better to sit back, bide his time, allowing his rivals to do the work.

“This offers a strong physiological advantage on the swim and the bike if you're drafting off other athletes, within race rules,” he says. “On the run, it's a small advantage physically, but more psychological.

“It’s a good tactic if you find yourself neck and neck with someone else. It's the Muhammed Ali rope-a-dope thing; acting like you’re weak and sand bagging a little bit.”

2. Play up a perceived weakness or look strong

Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak.― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

In his own words, Cody says he’s “not the prettiest runner”. This is true when he’s fresh, and even more so at back sections of Ironman courses. In certain situations, when he wants his rivals to believe he’s in worse shape than he really is, Cody accentuates his running style.

“I let my head wobble back and forth, throw my arms even wider, looking worse than in reality, when in fact that's just how I run,” he says. “This can get into another athlete’s head.”

Alternatively, the opposite ruse – looking stronger than you really are – is also advisable in certain situations.

“This is often something you do out in back sections of the run course,” Cody says. “Most triathlons feature sections like this where you can scope out the competition. I like to smile at my rivals, maybe give them a thumbs up. Or to really get inside their head, I might offer a word of encouragement, like a ‘good job’.”

3. Remember they are struggling, too

In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity― Sun-Tzu, The Art of War

In the heat of a race, when he’s really suffering, Cody likes to remind himself that his rivals are, too.

“I like to tell myself that they are suffering as much or more than I am,” he says. “Often you feel like you are locked in this titanic struggle all on your own. But it bears remembering that everyone else out there is also going through this. Remembering that gives me strength.”

4. Block them out

When the outlook is bright, bring it before their eyes; but tell them nothing when the situation is gloomy.― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

As a last resort, when things get really tough, Cody advises to turn inward.

“The other thing you can do is outright ignore them, pretend other athletes on the course don’t even exist,” he says. “This is a last resort. I think the most useful strategy is to engage the competition, to engage with the pain, to be very present and mindful about what is happening. However, as a last resort, you can detach from everything happening, including the competition, and turn your focus inwards.”

5. Prepare well for battle

Plan for what it is difficult while it is easy, do what is great while it is small.― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Intense competition can rattle even experienced pro athletes like Cody. That’s why he dedicates a significant amount of time to preparing for it.

“In pretty much all my difficult training sessions I will dedicate some time to visualisation, specifically around other athletes,” he explains. “If I know who I’m going to be racing, they will figure into my visualisation. I will practice a key moment involving that athlete and rehearse it again and again mentally. For example, I might go over a certain pass, where I'm going to drop them, or us locked in a finishing sprint. It’s extremely repetitive so when it comes to the actual moment in the race, it’s almost like a dream because I’ve practiced it so many time before.”

6. Make an alliance

If you do not seek out allies and helpers, you will be isolated and weak.― Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Once in a while, during a race that isn’t going well, and only in the bike stage, Cody says making an alliance with another athlete can sometimes be helpful.

“It’s always with an athlete who I think I can outrun, but who rides similarly to me,” he says. “If I think I can leverage that, and gain something by being cooperative on the bike by legally working together with the 12 m spacing, that’s worthwhile. It rarely works out in practice, but sometimes you can find yourself with one or two other athletes and it pays to work together.”

7 principles to help you find the flow

If there’s one way to get athletes talking, it’s to ask them about their flow experiences. They sit up, smile, and recall incredibly vivid experiences they will cherish for the rest of the lives. In many ways, flow states are the big reward that keep us going. Kind of like the panoramic view at the top of a mountain that makes the arduous climb worthwhile.

Flow states are a basic human potential. They are available to all of us, not only elite athletes, musicians and artists. With a little knowledge, dedication and practice, we can increase the likelihood of having a flow state experience.

According to mental coach Markus Arvaja, flow states are thoroughly immersive experiences. In his work with top ice hockey, football and tennis players, he tries to put in place the conditions that make flow states, when performance becomes almost effortless, more likely. Markus is a certified sports psychology consultant and senior lecturer in coaching at Finland’s Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences.

Click here to read our article explaining the science flow states!

No challenge, no flow

“First,” Markus says, “you need to have a feeling of being challenged, but that you have the competency and self confidence to handle it.” It’s a delicate balance. If the challenge is too great, and you feel out of your depth, lacking the skills for an activity, then it’s unlikely you will experience a flow state. There’s simply too much mental activity happening.

On the other hand, if the task is too easy, and the challenge is too low, then you are likely to be bored, also making flow state unlikely. The sweet spot is somewhere in the middle. So consider what might be a reasonable challenge for you, one that you feel confident in your skills and ability to take on.

Feel positive

The next essential condition for flow state experiences is motivation. “It helps if you can achieve your optimal arousal,” Markus explains. “You need to feel that you are really into the activity.” There’s another balance here. One extreme is boredom, the other is being too excited, almost nervous with anticipation. In the middle is relaxed enthusiasm. One way to achieve this is to remember the reasons you love your sport, what it gives you, a few minutes before you perform. Or maybe listening to music motivates you.

Automate the skill set

The reason top athletes and musicians experience flow is because they have put in the countless hours necessary to master their chosen activities. Whatever your sport, you need to have automated the skills required to experience flow. The action should come naturally from the body without any need for thinking or assessment. “If you don’t trust your technique, it’s hard to achieve the flow,” Markus says. “It’s important you train so much that you are well prepared and can get let go and let it happen. The moment you start to think too much, it’s hard to be in the flow.”

One thought at a time

Did we mention that thinking too much might obstruct a flow state? In the mindfulness movement, teachers talk about the “monkey mind”. Like we often jump from one thought to another, a monkey jumps from branch to branch incessantly. Constant thinking is tiring and distracting. “One good thing to do is to shift your focus to the activity at hand,” Markus says. “For example, if you are a tennis player, you could totally concentrate on moving your feet. It helps to concentrate on one or two things only. If you can do that, you might start to notice the flow. Just play the game and enjoy!”

Have a plan

Having a plan is very helpful, Markus says. For example, if you’re going to run a trail race, the plan might include having your own guidelines for pace, fuelling and heart rate. Well before the race, you might study the course, even train on it to get familiar, so on race day you know when to push and when to take it easy. “Make a plan at home,” Markus says. “That’s what we do in team sports. The less you think on the day, the better you perform.”

Practice mindfulness

“Mindfulness certainly helps,” Markus says. “If your mind is free of worry, and unnecessary thoughts, you can stay in the present moment. It’s good to learn to quiet the mind, to turn off the inner critic. Learn to simplify and focus on one thing.”

Play!

Yes, it’s important to have goals, to have a plan, to automate skills, and to be motivated. But if we get too serious, we risk getting too severe with ourselves and then the sport we once loved can feel like a strain. “Just play!” Markus always tells his clients. “It helps when you are positive and having fun. You can’t force the flow!”

Fuelling the engine: 6 principles of nutrition for athletes

When she's not in the mountains, you can find Emelie Forsberg in her garden or preparing delicious meals. © Matti Bernitz

How and what we eat is personal to each one of us. Some of us feel better and more energised by certain foods, while others feel quite differently. Regardless of our personal view, one thing we all have in common is that eating well is essential for top performance.

In our recent article series “Fuelling the engine” we heard from eight athletes and trainers about how they stay fuelled (see the end for the article list). What’s more interesting than their differences, is what they have in common. We’ve combed through and put together six basic principles of nutrition for athletes.

Find your rhythm

Suunto HQ is lucky to have in-house personal trainer and athlete Matias Anthoni walking around the office. He offers training and nutrition advice to whoever is interested. He says improving how often you eat can improve what you eat. Skipping meals is a no-no for dedicated athletes because it causes energy crashes and bad dietary decisions, which result in poor performance. He advises to get into a rhythm of having a healthy meal every three hours.

Get organized

To eat six or more well balanced meals a day demands forward planning. It’s pretty hard, if not impossible, to maintain this if you’re operating on a day-to-day basis. Ryan Sandes, Emelie Forsberg, Mel Hauschildt and Lucy Bartholomew all emphasised the importance of being well organised and planning ahead. They sometimes make extra portions of meals at the beginning of the week to have later in the week when they know they will be busy. Being organised means making sure there are plenty of easy, go-to meal ingredients available, too.

Balanced meals

There are a number of different aspects to having a balanced diet. Ultracycling man Omar di Felice sees it as maintaining a proper balance of carbohydrates, protein and fat, with fatty food being essential for his epic extreme rides above the Arctic Circle every winter. This balance of carbohydrates, protein and fat is what nutrition expert Dr. Rick Kattouf II also drills into his clients. He believes every meal – for dedicated athletes in training – should include this ratio: 50 to 60 % carbohydrates, 15 to 25 % protein, and 15 to 25 % fat. Balance also means eating a variety of foods to make sure you are taking in enough minerals and vitamins. Ski mountaineer Greg Hill tries to have a balance of colors in his meals.

Fresh is best

One thing that came through loud and clear from all our athletes and experts is the importance of eating fresh foods. For Emelie Forsberg and Lucy Bartholomew this means preferably straight out of the earth. As an avid gardener and farmer, Emelie grows and harvests much of what she eats. Lucy, ski mountaineer Greg Hill, Mel and Ryan all try to avoid eating packaged foods, instead choosing foods that are as close to the source of production as possible.

Whole is the goal

Should go without saying: avoid processed food and food with refined sugar. Instead, all our athletes opt for whole foods. Ryan Sandes questioned the idea that recovery shakes could ever replace the nutritional value of whole food. Don't take shortcuts; take the time to eat well. It’s self kindness.

Enjoy yourself

Emelie, Ryan and Greg all said they don’t get uptight about food. Emelie has a relaxed and intuitive approach to food, and Ryan and Greg are happy to allow themselves to enjoy a pizza or a burger each week. Greg cautions not to try to be perfect; aim to make the bulk of what you eat fresh and healthy. “It’s important to enjoy life as well,” Ryan says.

Click below to read articles in our Fuelling the Engine series:

Fuelling the engine: talking nutrition with Lucy Bartholomew

Fuelling the engine: talking nutrition with Emelie Forsberg

Fuelling the engine: a commonsense approach to nutrition

Fuelling the engine: talking nutrition with Ryan Sandes

Fuelling the engine: talking nutrition with Ultracycling Man

Fuelling the engine: talking nutrition with Mel Hauschildt

D.I.E.T (disaster imminent every time), and three unchanging principles of nutrition for athletes

Fuelling the engine: talking nutrition with Greg Hill

Lead images:

Photo by ja ma on Unsplash

© Craig Kolesky / Red Bull Content Pool